This church is dedicated, exotically, to St Margaret of Antioch – not the Antioch which is the present-day Antakya at the NE corner of the Mediterranean close to the Syrian border but that now-ruined ancient Antioch in south-west central Anatolia. At the end of the 3rd century, this Antioch was the capital of Roman Pisidia, a region already with strong links to the traditions of St Paul. According to the legend of St Margaret, it was in Pisidian Antioch where she suffered martyrdom during the persecutions of the late-3rd century.

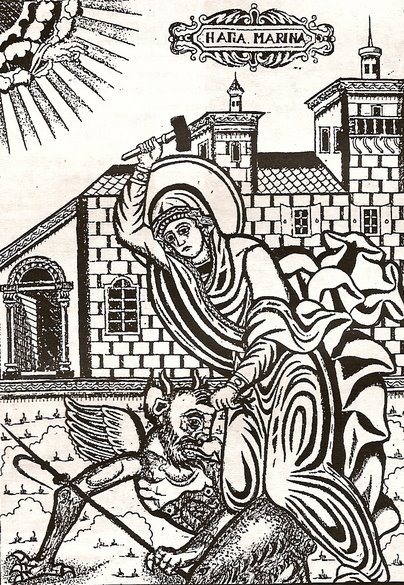

Our St Margaret (known to the Eastern Church as Marina) was one of six Margarets who, in mediaeval times, were venerated as saints and martyrs. It is reported that our St Margaret’s was one of the voices heard by Joan of Arc.

An account of St Margaret’s life (The Lyfe of Seint Margarete) has survived from the pen of the Benedictine monk and productive poet John Lydgate (c.1370–c.1451) – born in that Lidgate less than 2 miles N of the church.

Although it is generally agreed that the traditions surrounding the circumstances of St Margaret’s martyrdom are fictitious (her story was declared apocryphal as early as 494 by Pope Gelasius), hers was a popular cult in this country and especially in East Anglia: more than 200 churches were dedicated to her – not least because she offered protection in childbirth. In Lydgate’s Lyfe she shows humility by seeking no special powers for herself; instead, she appeals to God to act as intervening physician. As might be imagined, protection for expectant mothers was much valued in mediaeval times.

Mind you, the popular view that whoever dedicated a church to our St Margaret would find his prayers answered without fail must have been persuasive, too.

Of those churches dedicated to our St Margaret in this country, only some thirty have survived: we in Cowlinge are fortunate indeed to have one of those survivors – as, possibly, does the adjoining parish of Stradishall.

Exterior

Having walked up the broad path to the church, the visitor is faced with a curious and striking sight: a severe yet imposing 18th-century tower of red brick, standing against an endearingly unpretentious nave and chancel; a tower insensitively but confidently at odds with with the modest mediaeval church it serves.

Justification for the tower’s building was placed on record as the collapse of an earlier structure, raising various possibilities, all historically significant.

Completed in 1733, the bell-tower (‘steeple’, at the time of its building) is a fine example of that style known as ‘Classical’ (1700-1830), which continues to be favoured in this country – ask any estate agent.

Suffolk offers but limited building-stone – and no freestone. Brick was therefore favoured in this county. The exterior shows beautifully-executed brickwork in English Bond (chosen for its strength) and Flemish Bond (valued as a decorative technique) – both expensive. Suffolk has but three examples of brick church towers: Cowlinge has one of them.

Anyone seeking to study English brickwork would do well to become familiar not only with the tower but also this church’s varied collection of workmanlike brick buttressing.

The tower is a competently-built structure and although considered sound it is evident that attention to its lower courses of brick would be desirable. In addition, the W door needs treatment.

Our visitor, having completed his walk-around, might be excused were he to conclude that here is not so much a church as a gathering of sixteen disparate buttresses united by ecclesiastical association. For a small church, sixteen buttresses? – concern over structural stability, no doubt. But to determine the cause of structural instability would require research and, perhaps, structural investigation.

On the face of one of these buttresses may be found a tide-dial (‘tide’, from the Old English tīd, ‘due time’), a little sundial to indicate canonical hours. St Margaret’s tide-dial, however, requires that for this device to work, the sun must not only shine, but shine from underground – for our tide-dial is upside-down. Logical explanation? This tide-dial was removed from its original location and re-used in early-modern times merely as a facing-stone; but somehow an inverted tide-dial suits this little church. But where did this facing-stone, suggesting a context of ashlar, come from?

Entrance to the church, as it has been from at least the late-14th century, is through a porch on the N side of the building. Now, this is odd. First, because the N side of a church is not generally so favoured unless topography warrants; second, this main entrance does not face the present village. The porch, which has marked the main entrance to the church since its building in, probably, the 15th century returns us to the question of why the church is where it is. Was this always the main entrance? Well, as one enters the porch, to one’s right, below the little window, the stone is hollowed out, presumably to form a stoup for the dipping of fingers into holy water before entering the main building – thus a sign of the main entrance since late-mediaeval times.

But the stone-built porch itself repays inspection. The unglazed side windows which light the interior have mouldings executed not in stone but in brick; brick, too, frames the entrance with a round-headed opening, which originally would have had a door.

Nearly twenty years ago, inspection revealed that the porch roof was – and had been for some time – in very poor condition. Tiles were missing and those which remained in place were unevenly coursed: re-tiling was recommended. It was also noted that the porch was separating from the body of the church. Inspection in 2021 brought the recommendation not only for re-roofing but also that there be a structural check of the porch.

Today in 2024, the state of the little porch overall is yet further deteriorated: the brick entrance is now supported of necessity by Acrow steel propping. Overall, the time is approaching when the very survival of the porch will be a matter of concern.

Interior

Having entered the building, let us turn left and walk down the nave to the far end (the E end) of the church.

There, seen through a handsome wooden screen, is the chancel, the spiritual focus of the whole building. As it happens, the proportions of our chancel make this space unusually pleasing to the eye.

The chancel is where the altar stands. Nearly 500 years ago, altars were ordered to be destroyed and replaced by wooden tables. Even the word ‘altar’ was removed from the Prayer Book of 1552. Cowlinge still has its mandatory wooden table, which serves today as an altar within the enclosed chapel in the South aisle. But, remarkably, we may also have that original stone altar-top or mensa (Latin, ‘table’) which should have been broken up so long ago. During major restoration-work 1913–14, a stone slab, identified as the mensa, was found, serving as a floor-slab. This substantial stone was accordingly returned to its supposed intended location, where it remains today: the present altar top.

In the N wall of the chancel may be seen two intriguing anomalies: a small window – now blocked – and an outwards-opening doorway.

Against the N wall there is an 18th-century memorial of immodest proportions, flamboyantly – and a touch assertively – mispositioned.

This memorial commemorates in marble the London barrister, Francis Dickins (‘a shining Ornament to his Profession’, reads the inscription) who died in 1747; also his wife, Rachel. Both appear as Roman worthies. Mr Dickins it was who paid for (among other things) the W tower, which, like his monument, so nearly steals the show.

But this marble monument is worthy of note – because it came from the workshop of Peter Scheemakers or Scheemaekers (1691–1781). That name might ring a bell, for it was Scheemakers who was responsible for the Shakespeare memorial (and others) in Westminster Abbey. Originally from Antwerp, Scheemakers is held to be among England’s most important and influential sculptors: perhaps the most important and influential. And here in Cowlinge we have an example – an immoderately substantial example – of his work.

The Dickins monument, the only example of Scheemakers’ work to be found in Suffolk, needs attention. With damage spreading – damage brought about by concealed corroding ironwork within the monument – both repair and the expertise of a conservator are required.

In contrast to the ostentation of the Dickins monument, at the W end of the nave by the tower door there is a modest commemoration from the 1970s: a small plate – easily missed – attached to the wall. This is also in memory of two people and records that ‘The panelled screen enclosing the area under the gallery was removed’ (our italics).

Perhaps to future visitors, the contrast between the two memorials, one at the E, the other at the W end of the church, will bring a smile. Let us hope this little church and its fittings will survive for future visitors to be able to entertain such thoughts.

Moving to the W and looking back through the chancel arch, one sees that which the 1913-14 restoration revealed: a late-mediaeval secco wall-painting on lime-putty, today known as the Cowlinge Doom. This work is not well known: it is not cited, for example, among the examples named on at least one website listing English church wall-paintings; moreover, the Cowlinge Doom does not appear as a primary entry in Wikipedia. This is surprising, for it is one of the more curious of the genre.

To place this work in context: Dooms (Anglo-Saxon dom, ‘judgment; destiny’) were once a common subject included in church wall-paintings, to some degree with didactic purpose, from the 12th century until – with assorted justifications – they were deliberately destroyed or concealed under limewash, as at Cowlinge. Many were lost at the time of the Reformation in the 16th century and during the days of the Commonwealth in the century which followed. Fewer than 50 examples of Doom or Judgement church wall-paintings survive in this country. The destruction was thorough: we may have lost over 90% of examples of this subject of mediaeval church art.

It follows that any Doom wall-painting is automatically a national treasure; but of those Doom wall-paintings which survive, the Cowlinge Doom stands apart as unusual. Let us see why.

In those examples which have survived, the Risen Christ, who decides the fate of each soul, is the predominant figure; Sts Mary and John, as supplicants for the souls about to be judged, are shown as smaller, kneeling, figures. Other images, e.g., angels, St Peter and other apostles, devils or demons and symbols of Christ’s Passion frequently appear. The process of soul-selection may be undertaken by means of the Weighing of Souls, whereby the substance of each soul is measured against the burden of sin accrued during life. Meanwhile, devils or demons may seek to interfere with the process of selection by (for example) jumping into the ‘sin’ pan of the balance in the hope of enlarging the harvest of souls condemned to suffer eternity in Hell.

Let us, for a moment, consider how our Doom differs.

First, the Cowlinge Doom scene lacks the Risen Christ. Here is not the place to consider possible explanations; suffice to say, His absence opens a number of intriguing questions which are not exclusively iconographical but may also require consideration of the structural history of the building.

Second, the archangel Michael, here shown generously be-winged, bears weighing-scales – as one might expect from other examples which have survived. But in Cowlinge, the Weighing of Souls scene, normally a component of the Doom genre, is the main subject. As with the matter of the absence of the Risen Christ, one must apply the caveat that the structural history of the building may have a bearing on this apparent anomaly.

Third, and most significantly, by her actions the Virgin Mary dominates the scene. She is not merely attempting to intercede; she actively intervenes. Her instrument, a long staff with which she reaches across the apex of the chancel arch is tipping the scales in favour of the terrified soul, shown shrouded. St Mary is here successful: from the ‘sin’ pan of the scales, one devil at least appears to be bailing out.

The face of St Mary is formulaic in its rendering. The face of the archangel Michael is a touch more naturalistic: it displays both astonishment, presumably at the verdict of the scales (is he even aware of St Mary’s intervention?) and also delight. By contrast, the face of the shrouded soul – captured by but ten brush-strokes – is decidedly human. Is she perhaps a ‘from life’ memory?

Moreover, the manner in which the pigments were applied was considered by the 1991 conservation team to be unusual.

A thought prompted by the abnormalities of the Cowlinge Doom: what might the limewash on the walls to either side of this Weighing of Souls scene be covering?

When the wall-painting was inspected, cleaned and consolidated in 1991, disintegration of its surface was noted, disintegration likely to have been caused by water penetration. Cleaning, mild restoration and consolidation followed.

Recent inspection from floor level suggests however that for this late-mediaeval treasure time is running out. Despite the conservation-work carried out 33 years ago – which revealed that the method by which the wall-painting was exposed 1913–14 had been not only incomplete but also damaging – this remarkable work today appears, when viewed from the floor of the nave, to be threatened by water ingress, possibly from the leaking roof above.

The present state of the wall-painting of this rare, late-mediaeval treasure needs to be inspected closely and without delay. Such inspection will require scaffolding for access and the engagement of specialists to undertake the work.

The raising of funds for this undertaking became our first project. We can report success: a professional examination was carried out in May this year (2024).

But it would seem (subject to confirmation) that that the main threat to the wall-painting is the state of the roof above. In 2008, re-tiling was recommended as a matter of urgency; by 2014, the recommendation following inspection was for re-roofing. Seven years later, the condition of the tiling was reported to be ‘very poor’. Damp patches on the ceiling were noted. It was concluded that the roof was no longer capable of keeping out water. This, of course, has implications not merely for the wall-painting but for the structural health of the whole building.

Sorting out the church roofs will require serious money. Well, we’ve taken deep breaths and the search for funding has begun.

In 1961, St Margaret’s was listed as a Grade I monument and thus declared to be ‘of exceptional interest’. It is more than that.

We have seen above that this church is well endowed with those points of interest rightly beloved of church-guide writers and have briefly considered above some examples. But more remains to be explored: the handsome chancel-screen with (most unusually) its original iron fittings; a beautiful parclose with decorative carving in the S aisle; a further wall-painting on the S aisle wall;

an elegant W gallery (for the church band); the seating-provision recorded (benches remain in situ) for inmates of a local House of Correction established in the early 17th century; the original S and N doors – the latter presenting a lapstrake-like exterior appearance; the graffiti (chiefly mediaeval symbols, drawings and inscriptions, not all devotional) cut into the stonework, which continue to attract academic interest and for which this church is renowned.

But it is what goes unmentioned which makes this building worthy of nothing less than thorough and inter-related archaeological, structural and ecclesiological study. The entry for Cowlinge in Little Domesday records Cowlinge as not only a large and economically important settlement in the late-11th century but also as having an existing, i.e., pre-Conquest or ‘Saxon’, church. Does the present building occupy the site of this church? If it does, then why is the focus of the present village located so far from the first church?

The questions continue. The surface of the enigmatic structural history of this church has yet to be scratched: does the present church sit upon an earlier building? – its structural behaviour implied by the extensive buttressing over the years and its underpinning deemed necessary on the eve of the First World War suggests that it might. The earlier tower replaced in the 18th century: when was that built? The very location of this church raises the question: where was the focus of the pre-Conquest village? Moreover, given the believed population and economic importance of mediaeval Cowlinge, why is this church of such modest size?

As to this last question: even when aisles were added to the nave from the 14th century, this little church would have offered accommodation barely adequate for a settlement recorded in Domesday (1086) as both populous (40 households noted but there were probably more) and economically significant: Cowlinge was valued for tax purposes at 20 pounds 10 shillings – a considerable sum. In passing, one might note that by the time of official and systematic head-counting in the 19th century, the population of Cowlinge was about twice the size it is today.

This latter observation prompts recollection of the 2023 carol service. At a time when congregations have dwindled to such an extent that services are generally thinly attended and are held but once every seven weeks at Cowlinge (as in other churches within the benefice), on this occasion the church was very nearly filled – with families from Cowlinge.

Thus the church of St Margaret of Antioch at Cowlinge promises a significance broader than ecclesiastical architecture alone. Enchanting as it may be, this church offers more potential for information than might first appear.

© Derek Phillips 2024